It is top-down in the sense of taking the subjective (or what we could call experiential) features as point of departure for systematic exploration, all the time guided by the seemingly naïve method of numerous listening to any sound fragment and trying to depict what we are hearing.

This focus on sound objects and their perceptually salient features was, and still is, a remarkable development in music theory. These labels, largely related to motion shapes such as impulsive, iterative, sustained, rough, smooth, etc., grew out of practical composition work in the musique concrète and ensuing discussions at the Groupe de recherches musicales in Paris. Yet there was also an attempt to find some common features among individual experiences of sound objects by the use of metaphor labels. These perceptual images are largely influenced by our individual attitudes and schemas, including our attentional focus during listening. Although based on recorded fragments of sound, typically in the 0.5-5 s duration range, sound objects are actually perceptual images of these sound fragments, i.e., images in our minds of sound fragments we listen to. In parallel with the emergence of the musique concrète, Pierre Schaeffer and coworkers also dedicated much attention to the perceptual issues of this new kind of music, in particular to the so-called sound objects and their various features. This sound object theory makes extensive use of metaphors, often related to motion shapes, something that can provide holistic representations of perceptually salient, but temporally distributed, features in different kinds of music. Sound objects and their features became the focus of an extensive research effort on the perception and cognition of music in general, remarkably anticipating topics of more recent music psychology research. Furthermore, the term sound object was used to denote our perceptual images of such fragments. Centered in Paris around the composer, music theorist, engineer, and writer Pierre Schaeffer, this became known as musique concrète because of its use of concrete recorded sound fragments, manifesting a departure from the abstract concepts and representations of Western music notation. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, there emerged a radically new kind of music based on recorded environmental sounds instead of sounds of traditional Western musical instruments. 2RITMO Centre for Interdisciplinary Studies in Rhythm, Time and Motion, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway.1Department of Musicology, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway.There was no information available on his survivors.

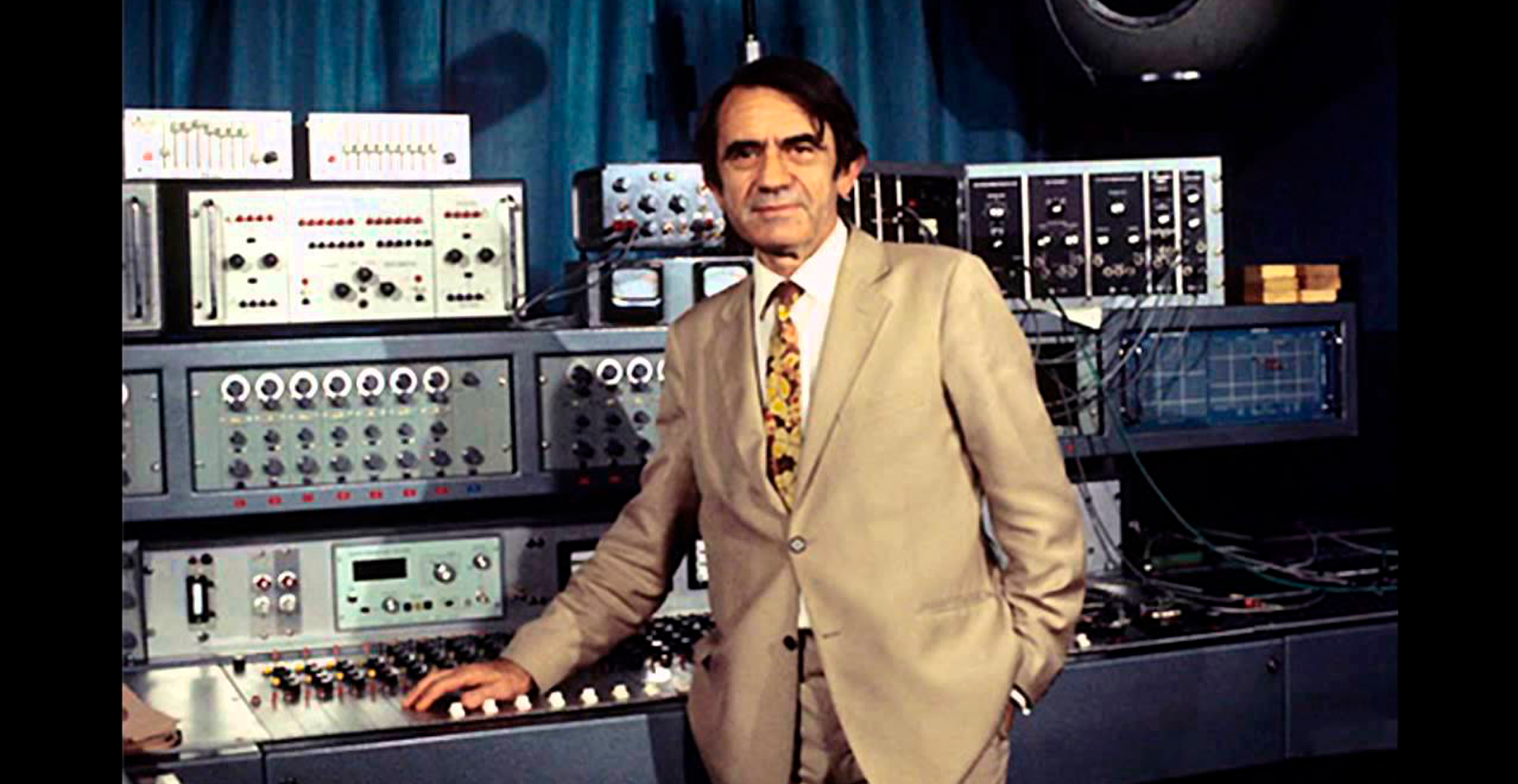

Musique conrete archive#

Henry donated his archive to France’s National Library. Henry’s “Intérieur/Extérieur,” the Philips label invited the duo Coldcut, William Orbit, Fatboy Slim and other artists to do remixes of “Mass for Today.” The results were released on the album “Metamorphosis.”

Henry paid homage to the Italian futurist Luigi Russolo, the author of the manifesto “The Art of Noises.” “Beethoven’s Tenth Symphony,” from 1979, knitted together isolated chords, arpeggios and rhythmic components from Beethoven’s nine symphonies into a single grand tribute. In the large-scale work “Futuristie,” written with the Canadian composer Bernard Bonnier, Mr.

Musique conrete series#

He began using electronic music in “Coexistence” (1958) and “Investigations” (1959), and in the 1960s embarked on a series of meditative compositions, including “Liverpool Mass” (1968), commissioned for the consecration of the Cathedral of Christ the King, and “The Apocalypse of John” (1968). Henry broke with French Radio and Television and, with the sound engineer Jean Baronnet, created the first private electronic studio in France. He also wrote the soundtrack for Jean Grémillon’s short film “Astrology, or the Mirror of Life” (1952), the first time musique concrète was used in the cinema. Henry wrote “The Well-Tempered Microphone,” “Variations for a Door and a Sigh” and “The Ambiguities Concerto” for piano,” which combined natural and altered piano sounds. Henry as a percussionist for the studios of French Radio and Television and invited him to join the Club d’Essai (Experimental Club), which Mr. He took harmony classes taught by Olivier Messiaen, at which Pierre Boulez was a fellow student. Before his 10th birthday he entered the Paris Conservatory, where, before and after World War II, he studied piano and percussion with Félix Passeronne and composition with Nadia Boulanger.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)